Bridging Theory and Practice in Global Health Education: Lessons from a Quality Improvement Project in Uganda

by Greta Handing

With dreams of expanding access to surgery in low-resource settings, I enrolled in a global health master’s program at Karolinska Institutet. My classmates and I, representing over 20 different countries, learned about sustainable development through lectures, group projects, and lively debates. Despite our diverse education, I found myself questioning the limitations of learning in a high-income country classroom. So, when the opportunity arose to travel to Uganda as part of the Action leveraging evidence to reduce perinatal mortality and morbidity (ALERT) project, I eagerly signed on, unsure what to expect.

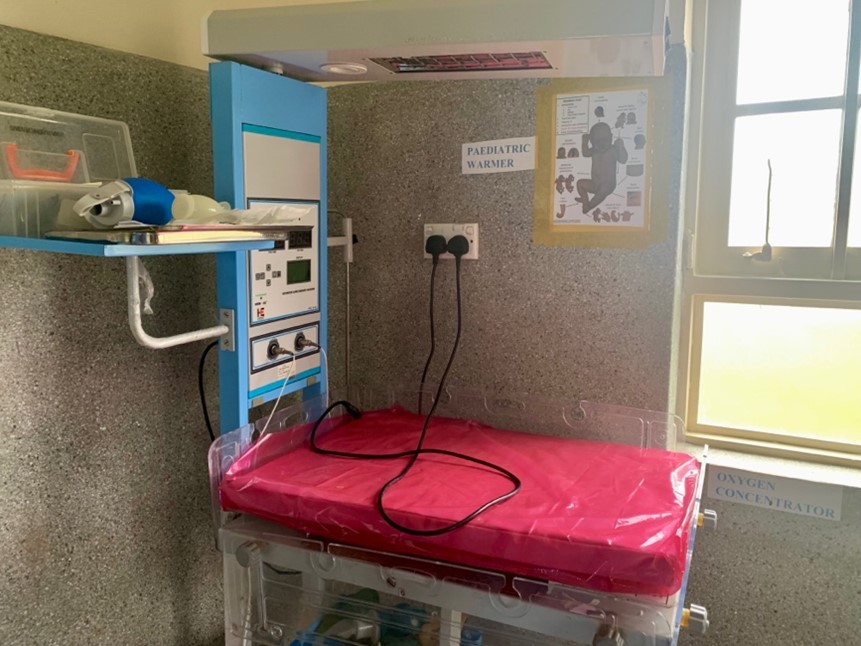

Birth defects are an important indicator of maternal and newborn health. For example, specific birth defects can indicate nutritional deficits. But very often, birth defects are underreported in much of Uganda. To improve identification and reporting at a regional referral hospital, I was tasked to create a training manual for healthcare workers in the neonatal care unit (NCU) under the assumption that diagnosis is made there. Clutching my entry ticket—a welcome letter from the hospital director—I was greeted by a line of donated incubators and makeshift respiratory support machines. After spending time with the NCU team, I quickly realized that we were mistaken about our assumption that the NCU was the source of the problem of underreporting.

Determined to find the real root of the issue, I sought out the labor and delivery ward. Overwhelmed by the organized chaos that oversaw the births of more than 2,500 babies every year, I relied heavily on conversations with various health professionals and trainees to understand the system. Together, we uncovered a crucial gap—omission of routine neonatal exams. Midwives burdened with post-labor care lacked the time to perform these exams and left the responsibility to trainees without proper skills and experience. Unaware of the importance of the exam, trainees often omitted it.

With valuable input from hospital staff and ALERT team members, I designed an educational poster outlining the steps of routine newborn care, with a specific emphasis on integrating the neonatal exam. The poster featured visual representations of abnormal exam findings using material available from the WHO. The pictures were thought to enable inexperienced providers to identify them accurately. With permission from ward leadership, I hung these posters at every delivery station as a visual reminder to prioritize and document the exam.

Although the long-term impact of this intervention remains to be seen, it left me with a changed perception and deeper motivation to work in global health. Distant knowledge and numbers cannot by themselves solve the problems holding back so many people around the world. An understanding of local contextual intricacy is key to meaningful improvements. Perhaps even more important, is collaboration. I witnessed firsthand the power of drawing equitably on the strengths and expertise of both local and international stakeholders.

By stepping outside the classroom, we gain invaluable insight into understanding different perspectives, fostering collaboration, and yielding better healthcare outcomes for those in need. While the ethical implications of implementation work in low-income countries persist and are beyond the scope of this essay, I believe that projects like this one can create humble, respectful, and genuine global health leaders and collaborators who are motivated to contribute to building a better future for all.

0 comments